Julio Llópiz-Casal — Caja China @ Efficiency (after Papanek)

@ Alibi (organized by the Forma Foco collective and ENTRE)

@ On the new. Viennese Scenes and Beyond

@ Belvedere 21 Museum of Contemporary Art

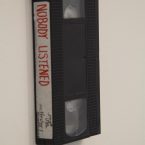

We are pleased, in this fifth iteration of Efficiency (after Papanek), to present the works of the artist and designer Julio Llópiz-Casal. For his exhibit, Caja China,[1] we have chosen four typologies of his work: A selection from his Instagram series aforismos ensartados[2]; an edition of twelve threshold portraits of political prisoners from 11J[3] (https://justicia11j.org/); one of his VHS tape works (Nobody Listened); and two shoes that have been intervened (Cómo llegó la noche y La noche no será eterna)[4]. Together the collection reveals the variety of media and supports Julio employs, simultaneously drawing attention to the reiteration of certain linguistic procedures and tactical operations that permit him both to reflect immediately on the political reality of Cuba—plus its international ripples—as well as on the diffusion and condemnations of the injustices and lack of rights on the island. Llópiz-Casal makes use of the vectors and voids of meme culture, as well as its logics, just as he takes advantage of serialized objects that can be customized and titled—audio and video tapes, floppy discs, among others. By infiltrating those voids, and with gestures as simple as writing a title on the label of a video tape whose contents are unknown to us, Julio seems to rethink the emancipatory potential of cultural devices. His titles, generally speaking, come from historical works and processes that have been systematically censored, obliterated, and stigmatized by the current totalitarian regime in Cuba. In this sense, his works are mnemonic shortcuts to another narrative, and toward the ideal civic context founded—in the future—on his interpretations.

The operations that Julio carries out refer back to the principle of the proxy object, or placeholder, used in graphic design and computing. The term was used in graphic design to designate the black rectangles that, in the prepress files, provisionally occupied the spaces destined for illustrations and photographs. In computing, the term is used to refer to the back-up characters that hold the space of a required but absent typography (ASCII). Synonymous terms are: Proxy, vicar[5], substitute, surrogate, replacement, ersatz. A placeholder is an object that provisionally occupies an empty space in a structure—whether it be a text, a discourse, a political or urban organization. The pope, the “Holy Vicar,” would be Christ’s placeholder on Earth. Many of the objects created in the 90s in Cuba to alleviate the economic crisis, after the fall of the Berlin Wall, were vicarious [i.e., substitute] objects that occupied the place of other objects—now absent—in daily life. We can ask ourselves: What political potentialities reside in the placeholder image when it temporarily occupies a space, whether a graphic surface, a physical space, or a discourse? The placeholder is that tactical object that, upon inserting itself, contaminates, corrupts, strengthens, amplifies, or questions the space it occupies. What relations, and what questions, are put forth by the works of Julio Llópiz-Casal when they temporarily occupy our exposition space?

The exhibition of Julio Llópiz-Casal’s Caja China in Efficiency (after Papernak) takes place within the frame of the exhibition Alibi, organized by the Forma Foco collective and ENTRE for the exhibition On the new. Viennese Scenes and Beyond at Belvedere 21 Museum of Contemporary Art.

[1] The “caja china” referred to here is the literary technique of placing one story within another that is within another and so on. (Also known as “Russian Dolls.”)

[2] “strung aphorisms.”

[3] In reference to the 11th of July (2021), also known as the 2021 Cuban Protests, or simply as 11J, in spanish.

[4] “How the night came” and “The night will not last forever.”

[5] In its etymological sense of “substitute” or “surrogate.”

- Alibi general view. Photo: Kevin Avila

- Alibi general view. Photo: Kevin Avila

- Alibi general view. Photo: Kevin Avila

- Alibi general view. Photo: Kevin Avila

- Alibi general view. Photo: Kevin Avila

- Julio Llópiz-Casal, intervened shoes “How the night came” and “The night will not last forever,” 2023, photo: Kevin Avila

- Julio Llópiz-Casal, intervened shoes “How the night came” and “The night will not last forever,” 2023, photo: Kevin Avila

- Effciency (After Papanek) exhibiting Caja China by Julio Llopiz-Casal. Photo: Kevin Avila

- Effciency (After Papanek) exhibiting Caja China by Julio Llopiz-Casal. Photo: Kevin Avila

- Alibi general view. Photo: Kevin Avila

- Julio Llópiz-Casal at Efficiency, detail. Photo: Kevin Avila

- Julio Llópiz-Casal, intervened VHS tape (Nobody Listened), 2023, photo: Kevin Avila

- Julio Llópiz-Casal, #aforismosensartados, 2020-ongoing, digital print on polyester.

- Julio Llópiz-Casal, #aforismosensartados, 2020-ongoing, digital print on polyester.

- Julio Llópiz-Casal. Portraits of political prisoners from 11J. Encapsulated digital print. A loose leaf publication, 15 pages.

- Julio Llópiz-Casal. Portraits of political prisoners from 11J. Encapsulated digital print. A loose leaf publication, 15 pages.

- Julio Llópiz-Casal. Portraits of political prisoners from 11J. Encapsulated digital print. A loose leaf publication, 15 pages.

- Julio Llópiz-Casal. Portraits of political prisoners from 11J. Encapsulated digital print. A loose leaf publication, 15 pages.

- Julio Llópiz-Casal. Portraits of political prisoners from 11J. Encapsulated digital print. A loose leaf publication, 15 pages.

- Julio Llópiz-Casal. Portraits of political prisoners from 11J. Encapsulated digital print. A loose leaf publication, 15 pages.

- Julio Llópiz-Casal. Portraits of political prisoners from 11J. Encapsulated digital print. A loose leaf publication, 15 pages.

- Julio Llópiz-Casal. Portraits of political prisoners from 11J. Encapsulated digital print. A loose leaf publication, 15 pages.

- Julio Llópiz-Casal. Portraits of political prisoners from 11J. Encapsulated digital print. A loose leaf publication, 15 pages.

- Julio Llópiz-Casal. Portraits of political prisoners from 11J. Encapsulated digital print. A loose leaf publication, 15 pages.

- Julio Llópiz-Casal. Portraits of political prisoners from 11J. Encapsulated digital print. A loose leaf publication, 15 pages.

- Julio Llópiz-Casal. Portraits of political prisoners from 11J. Encapsulated digital print. A loose leaf publication, 15 pages.

- Julio Llópiz-Casal. Portraits of political prisoners from 11J. Encapsulated digital print. A loose leaf publication, 15 pages.

- Julio Llópiz-Casal. Portraits of political prisoners from 11J. Encapsulated digital print. A loose leaf publication, 15 pages.

- Julio Llópiz-Casal. Portraits of political prisoners from 11J. Encapsulated digital print. A loose leaf publication, 15 pages.

more info:

ALIBI_press_release

https://www.instagram.com/juliollopizcasal/

https://www.instagram.com/forma.foco

Forma Foco: Aminta D’Cárdenas, Julio Llopiz-Casal, Lester Alvarez, Solveig Font

En esta quinta iteración de Efficiency (after Papanek) nos complace presentar el trabajo del artista y diseñador Julio Llópiz-Casal. Para su muestra Caja China hemos escogido cuatro tipologías de obras: una selección de su serie para Instagram aforismos ensartados; una edición de doce retratos de presos políticos del 11J (https://justicia11j.org/); uno de sus trabajos con casetes VHS (Nobody listened); y dos zapatos intervenidos (Cómo llegó la noche y La noche no será eterna). El conjunto muestra la variedad de medios y soportes empleados por Julio, al mismo tiempo que señala la reiteración de ciertos procedimientos de lenguaje, y operaciones tácticas que le permiten, tanto la reflexión inmediata sobre la realidad política de Cuba-y las derivas internacionales de esta realidad, como la difusión y denuncia de las injusticias y faltas de libertades en la isla. Llópiz-Casal se vale de vectores y vacíos, propios de la cultura même, y de sus lógicas, así como de aquellos objetos seriados que pueden ser customizados, titulados, como los audio y videos casetes, floppy discs, entre otros. Con la infiltración en esos vacíos, y con gestos tan sencillos como escribir un título en la etiqueta de un casete de video, cuyo contenido desconocemos, Julio parece repensar la potencialidad emancipatoria de los dispositivos culturales. Sus títulos provienen, por lo general, de obras y procesos históricos sistemáticamente censurados, obliterados y estigmatizados por el actual régimen totalitario de Cuba. En este sentido sus obras son atajos mnemotécnicos hacia otra narrativa, y hacia el contexto cívico ideal fundado, en el futuro, por su interpretación.

Las operaciones que Julio activa remiten al principio del objeto proxi o placeholder, utilizado en diseño gráfico e informática. El término se empleaba en diseño gráfico para denominar los rectángulos negros que ocupaban, provisionalmente, en los archivos de preimpresión, las zonas destinadas a ilustraciones y fotografías. En informática se usa para los caracteres de reemplazo que ocupan el lugar de una tipografía requerida pero ausente (ACIIS). Términos sinónimos son: proxi, vicario, sustituto, surrogate, sucedáneo, ersatz. Un placeholder es un objeto que ocupa provisionalmente un espacio vacío en una estructura, esta puede ser un texto, un discurso, una organización urbana o política. El papa, el “santo vicario”, sería el placeholder de Cristo en la tierra. Muchos de los objetos creados en Cuba en los años 90’ para aliviar la crisis económica, tras la caída del muro de Berlín, eran objetos vicarios, que ocupaban el lugar en la vida cotidiana de otros objetos, ahora ausentes. Podemos preguntarnos, ¿qué potencialidades políticas residen en la imagen placeholder, cuando ocupa temporalmente un espacio, ya sea una superficie gráfica, un espacio físico o un discurso? El placeholder es ese objeto táctico que, al insertarse, contamina, corrompe, potencia, amplifica o cuestiona el espacio que ocupa. ¿Qué relaciones, y qué preguntas, propone la obra de Julio Llópiz-Casal cuando ocupa temporalmente nuestro espacio expositivo?

La exhibición Caja China de Llópiz-Casal en Efficiency (after Papanek), ocurre en el marco de la exhibición Alibi, organizada por el colectivo Forma Foco y por ENTRE, para la exhibición On the New. Viennese Scenes and Beyond, en Belvedere 21 Museum of Contemporary Art.