Reparación como ruptura III 🙂, 2022 (scroll down for english version)

Una funda de batidora es una tipología contemporánea de objeto. En este sentido, no es distinta de la batidora que cubre.

La finalidad de este objeto es profiláctica: se espera que el forro proteja del polvo y de otros agentes corrosivos las partes frágiles y superficies de la batidora. Estas fundas, hechas con retazos de telas, cintas de encaje, bordados y cuerdas, se hallan en hogares de Cuba, Colombia, Brasil, y es probable que en los de muchos otros países y territorios con similares prácticas culinarias y costos de vida. En posts y comentarios de Facebook, y de otros foros de internet donde abundan fotos de este dispositivo, se le nombra indistintamente como “vestido de batidora”, “ropa de batidora”, “bata de batidora”, “forro de batidora” y “funda de batidora”. La idea de protección es recurrente en las descripciones, así como la mención al rol de embellecer.

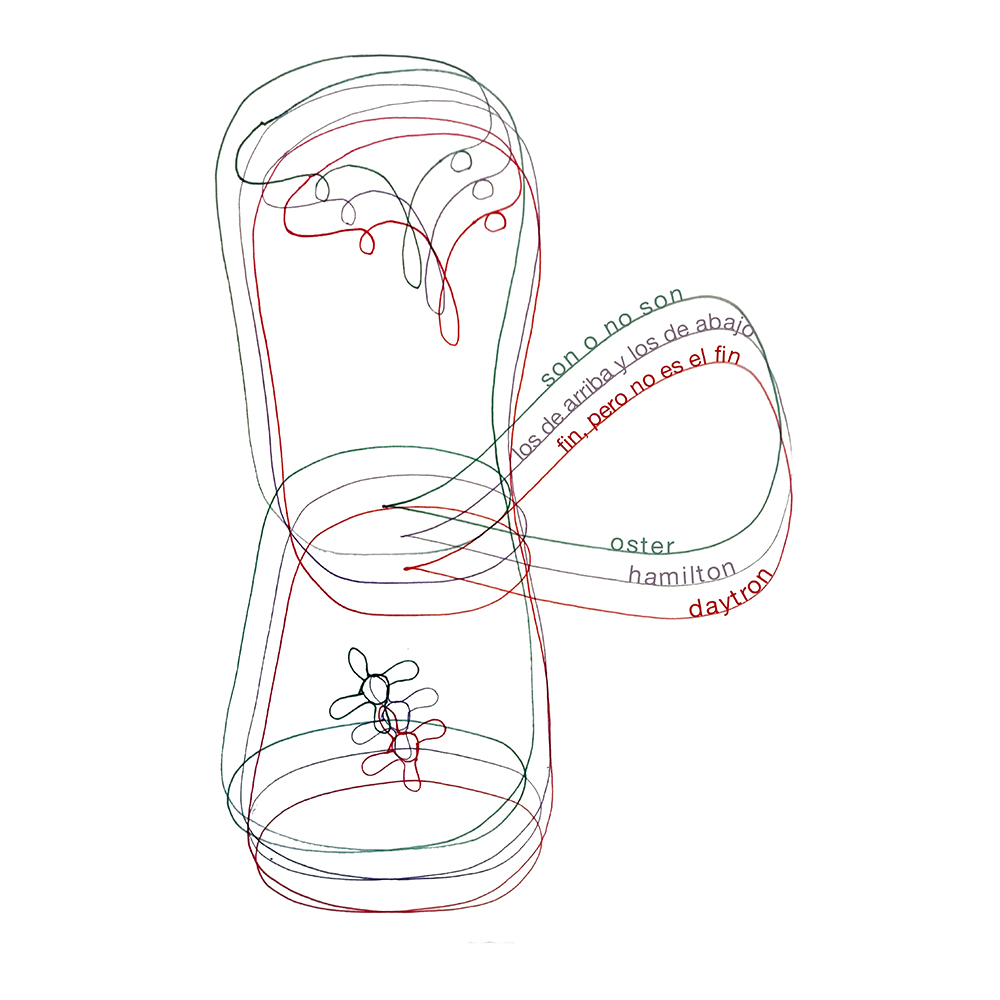

El impulso profiláctico inicial da paso, durante su confección, a una exploración formal que se distancia de las líneas minimalistas y empleo de materiales que hoy tienen todas las batidoras, sean Daytron, Hamilton, Kenwood, Man, Oster, Philips o Vince. ¿Quién puede reconocer la marca o el fabricante oculto detrás de esa vestidura? Los dos volúmenes principales que dividen el objeto cambian de proporción con relación al modelo que cubren, por lo que un ojo experto pudiera distinguir una batidora rusa de una coreana sin remover el vestido. “La rusa”, por ejemplo, tiene un vaso alto y una base más cónica que las batidoras modernas.

Es común que el deseo de proteger la batidora se acompañe de una necesidad de preservar la cafetera, la olla arrocera, el balón de gas. La silueta o estructura de las fundas, los estampados y las decisiones de color, se imponen sobre los rasgos distintivos de las marcas. Las fundas afirman una identidad nueva. Al aplicarse a varios objetos de la cocina, el conjunto se presenta como una familia nueva, aun cuando cubren artefactos de distintos fabricantes.

Todas las fundas de batidoras tienen caras. Cuando encuentro una foto de una funda de batidora sin rostro, pienso que no puedo observarlo porque nos da la espalda, o porque los rasgos de su cara se confunden con el estampado.

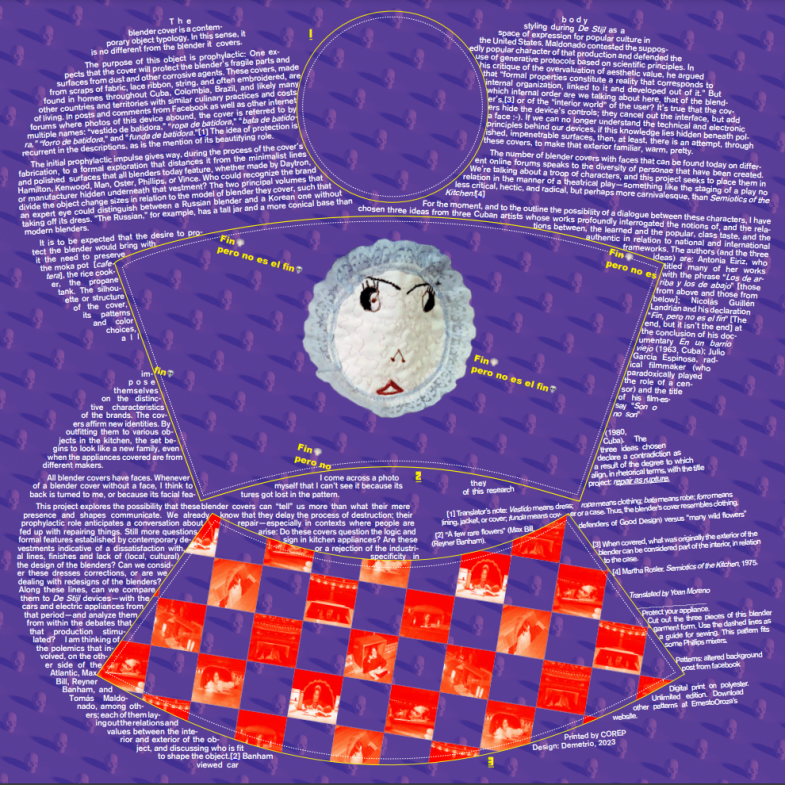

Este proyecto explora la posibilidad de que estas fundas de batidoras puedan “decirnos” más cosas que las que comunican con su mera presencia y formas. Ya sabemos que retrasan el proceso de destrucción; su rol profiláctico se adelanta a una conversación sobre la reparación— especialmente en contextos donde la gente está hastiada de reparar. Pero otras preguntas arriban. ¿Cuestionan estas fundas las lógicas y los rasgos formales asentados por el diseño contemporáneo para los electrodomésticos de cocina? ¿Son las vestiduras índices de una insatisfacción o inconformidad con las líneas y acabados industriales, y con la poca especificidad (local, cultural) del diseño de la batidora? ¿Pódemos considerar estos vestidos correcciones, o se trata de rediseños de las batidoras? En este sentido, ¿pódemos compararlos con los artefactos del styling, con los autos y electrodomésticos de ese período, y analizarlos desde los múltiples debates que esa producción estimuló? Pienso en las polémicas que involucraron, al otro lado del Atlántico, a Max Bill, Reyner Banham, Tomás Maldonado, entre otros. Cada uno de ellos estableciendo relaciones y valores entre el interior y el exterior del objeto, y discutiendo quién está apto para dar forma al objeto[1]. Banham veía las carrocerías de autos durante el styling como un espacio de expresión para la cultura popular en Estados Unidos. Maldonado discutía el supuesto carácter popular de esa producción, y defendía el uso de protocolos generativos basados en principios científicos. En su crítica a la sobredimensión del valor estético, sostenía que “las propiedades formales constituyen una realidad que se corresponde a su organización interna vinculada a ella y desarrollada a partir de ella”. Pero, ¿de cuál orden interno estaríamos hablando aquí, el de la batidora*, o el “mundo interior” del usuario? Es cierto que los forros ocultan los controles del artefacto, cancelan la interface pero añaden una cara :-). Si ya no podemos entender los principios técnicos y electrónicos de nuestros artefactos, si estos conocimientos yacen ocultos tras formas púlidas e impenetrables, al menos se intenta, con estos forros, que ese exterior nos sea familiar, cálido, bonito.

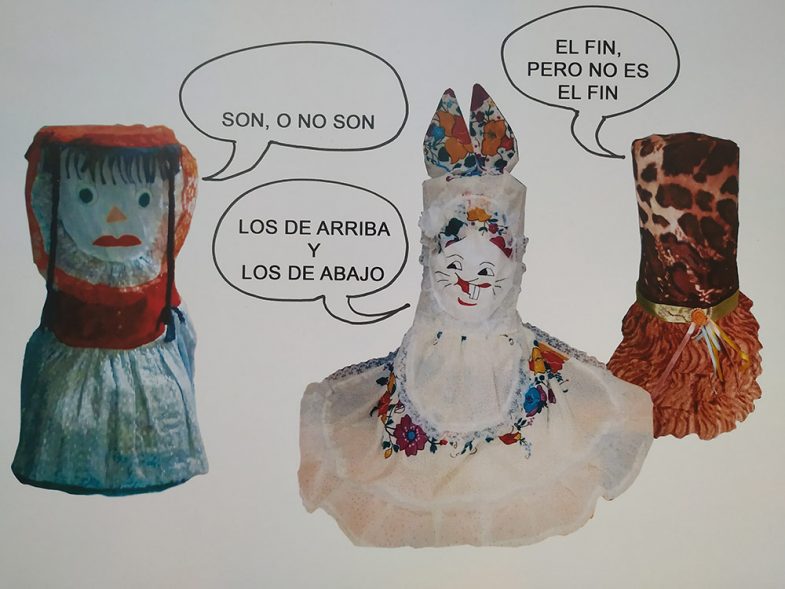

La cantidad de forros de batidoras con rostros que pueden hallarse hoy en distintos foros online da cuenta de la diversidad de caracteres que han sido creados. Estamos hablando de una tropa de personajes, y este proyecto busca ponerlos en relación a modo de una obra de teatro. Algo así como una puesta teatral, no menos crítica, agitada y radical, pero quizás más carnavalezca, de Semiotis of the kitchen[2]!

Por el momento, y para enunciar la posibilidad de un diálogo entre estos personajes, he seleccionado tres pensamientos de tres artistas cubanos cuyas obras indagaron profundamente en nociones y relaciones entre lo culto y lo popular, el gusto de clase, lo auténtico en relación al marco de lo nacional e internacional. Los autores (y los tres pensamientos) son: Antonia Eiriz, quien tituló varias de sus obras con la frase “Los de arriba y los de abajo”; Nicolás Guillen Landrián y su declaración “Fin, pero no es el fin” al cierre de su documental En un barrio viejo (1963, Cuba); Julio García Espinosa cineasta radical (quien paradójicamente jugó un rol de censor) y el título de su filme-ensayo “Son, o no son” (1980, Cuba). Los tres pensamientos seleccionados enuncian una contradición por lo que sintonizan, en términos retóricos, con el título de este proyecto: Repair as rupture.

[1] “A few rare flowers” (Max Bill, defensores del Good Design ) vs “many wild flowers” (Rayner Banham)

* Cuando está cubierto, el exterior original de la batidora se puede considerar parte del interior, en relación a la funda.

[2] Martha Rosler – Semiotics of the Kitchen 1975

Repair as Rupture III :-), 2022

The blender cover is a contemporary object typology. In this sense, it is no different from the blender it covers.

The purpose of this object is prophylactic: One expects that the cover will protect the blender’s fragile parts and surfaces from dust and other corrosive agents. These covers, made from scraps of fabric, lace ribbon, string, and often embroidered, are found in homes throughout Cuba, Colombia, Brazil, and likely many other countries and territories with similar culinary practices and costs of living. In posts and comments from Facebook as well as other internet forums where photos of this device abound, the cover is referred to by multiple names: “vestido de batidora,” “ropa de batidora,” “bata de batidora,” “forro de batidora,” and “funda de batidora.”[1] The idea of protection is recurrent in the descriptions, as is the mention of its beautifying role.

The initial prophylactic impulse gives way, during the process of the cover’s fabrication, to a formal exploration that distances it from the minimalist lines and polished surfaces that all blenders today feature, whether made by Daytron, Hamilton, Kenwood, Man, Oster, Phillips, or Vince. Who could recognize the brand or manufacturer hidden underneath that vestment? The two principal volumes that divide the object change sizes in relation to the model of blender they cover, such that an expert eye could distinguish between a Russian blender and a Korean one without taking off its dress. “The Russian,” for example, has a tall jar and a more conical base than modern blenders.

It is to be expected that the desire to protect the blender would bring with it the need to preserve the moka pot [cafetera], the rice cooker, the propane tank. The silhouette or structure of the cover, its patterns and color choices, all impose themselves on the distinctive characteristics of the brands. The covers affirm new identities. By outfitting them to various objects in the kitchen, the set begins to look like a new family, even when the appliances covered are from different makers.

All blender covers have faces. Whenever I come across a photo of a blender cover without a face, I think to myself that I can’t see it because its back is turned to me, or because its facial features got lost in the pattern.

This project explores the possibility that these blender covers can “tell” us more than what their mere presence and shapes communicate. We already know that they delay the process of destruction; their prophylactic role anticipates a conversation about repair—especially in contexts where people are fed up with repairing things. Still more questions arise: Do these covers question the logic and formal features established by contemporary design in kitchen appliances? Are these vestments indicative of a dissatisfaction with, or a rejection of the industrial lines, finishes and lack of (local, cultural) specificity in the design of the blenders? Can we consider these dresses corrections, or are we dealing with redesigns of the blenders? Along these lines, can we compare them to De Stijl devices—with the cars and electric appliances from that period—and analyze them from within the debates that that production stimulated? I am thinking of the polemics that involved, on the other side of the Atlantic, Max Bill, Reyner Banham, and Tomás Maldonado, among others; each of them laying out the relations and values between the interior and exterior of the object, and discussing who is fit to shape the object.[2] Banham viewed car body styling during De Stijl as a space of expression for popular culture in the United States. Maldonado contested the supposedly popular character of that production and defended the use of generative protocols based on scientific principles. In his critique of the overvaluation of aesthetic value, he argued that “formal properties constitute a reality that corresponds to internal organization, linked to it and developed out of it.” But which internal order are we talking about here, that of the blender’s,[3] or of the “interior world” of the user? It’s true that the covers hide the device’s controls; they cancel out the interface, but add a face :-). If we can no longer understand the technical and electronic principles behind our devices, if this knowledge lies hidden beneath polished, impenetrable surfaces, then, at least, there is an attempt, through these covers, to make that exterior familiar, warm, pretty.

The number of blender covers with faces that can be found today on different online forums speaks to the diversity of personae that have been created. We’re talking about a troop of characters, and this project seeks to place them in relation in the manner of a theatrical play—something like the staging of a play no less critical, hectic, and radical, but perhaps more carnivalesque, than Semiotics of the Kitchen![4]

For the moment, and to the outline the possibility of a dialogue between these characters, I have chosen three ideas from three Cuban artists whose works profoundly interrogated the notions of, and the relations between, the learned and the popular, class taste, and the authentic in relation to national and international frameworks. The authors (and the three ideas) are: Antonia Eiriz, who titled many of her works with the phrase “Los de arriba y los de abajo” [those from above and those from below]; Nicolás Guillén Landrián and his declaration “Fin, pero no es el fin” [The end, but it isn’t the end] at the conclusion of his documentary En un barrio viejo (1963, Cuba); Julio García Espinosa, radical filmmaker (who paradoxically played the role of a censor) and the title of his film-essay “Son, o no son” (1980, Cuba). The three ideas chosen declare a contradiction as a result of the degree to which they align, in rhetorical terms, with the title of this project: repair as rupture.

[1] Translator’s note: Vestido means dress; ropa means clothing; bata means robe; forro means lining, jacket, or cover; funda means cover or a case. Thus, the blender’s cover resembles clothing.

[2] “A few rare flowers” (Max Bill, defenders of Good Design) versus “many wild flowers” (Reyner Banham).

[3] When covered, what was originally the exterior of the blender can be considered part of the interior, in relation to the case.

[4] Martha Rosler. Semiotics of the Kitchen, 1975.